Genetics 3H

Apis mellifera mellifera - Evolution of Ecotypes

The map on the previous page shows how Apis mellifera mellifera was originally distributed across Europe from Ireland to Russia. It goes without saying that there is an enormous change not only in climate but in the physical environment which the bees would experience. The black bee has been replaced in most areas leaving only isolated pockets in each of which over time an ecotype has evolved. An ecotype being a variant in which the phenotypical differences in the honey bee are too few or too subtle to warrant being classified as a subspecies.

A honey bee ecotype can be regarded as micro-subspecies with its own specific characteristics which reflect its adaptation to a local environment.

All bee colonies develop a strategy which ensures their survival. Colonies must adapt of perish. The main factors to which colonies must adapt can be summarized as follows:

The annual weather pattern and other factors will determine what brood pattern the queen adopts.

There is a tremendous variation in the weather pattern across the northern parts of Europe with which the black bee has to cope, from the cool maritime summer climate on the western seaboard to Russian winters.

One characteristic which the bees adopt is for the queen to start laying late in the spring with an early cessation of egg laying in the autumn.

Forage availability; this clearly depends on the type of plants available: heather on heath areas, trees in a forest, open grassland with wild flowers.

Prepare for winter. Nectar and pollen must be readily available for the bees to collect in the autumn to ensure adequate stores for the long winter ahead. Ivy and heather play an important role here.

Ability to cope with disease.

The black bee has ability to fly in cool weather particularly for the queen to mate. This is important in so far the black bee is able to self isolate when drones from other subspecies are present.

Each ecotype develops a unique brood pattern over the season

A honey bee ecotype can be regarded as micro-subspecies with its own specific characteristics which reflect its adaptation to a local environment.

All bee colonies develop a strategy which ensures their survival. Colonies must adapt of perish. The main factors to which colonies must adapt can be summarized as follows:

The annual weather pattern and other factors will determine what brood pattern the queen adopts.

There is a tremendous variation in the weather pattern across the northern parts of Europe with which the black bee has to cope, from the cool maritime summer climate on the western seaboard to Russian winters.

One characteristic which the bees adopt is for the queen to start laying late in the spring with an early cessation of egg laying in the autumn.

Forage availability; this clearly depends on the type of plants available: heather on heath areas, trees in a forest, open grassland with wild flowers.

Prepare for winter. Nectar and pollen must be readily available for the bees to collect in the autumn to ensure adequate stores for the long winter ahead. Ivy and heather play an important role here.

Ability to cope with disease.

The black bee has ability to fly in cool weather particularly for the queen to mate. This is important in so far the black bee is able to self isolate when drones from other subspecies are present.

Each ecotype develops a unique brood pattern over the season

In recent years these has been a renewed interest in the survival of the local bee with projects

aimed at conserving the natural heritage of local populations, with on-going projects in several European countries. In a research paper published by COLOSS in 2014

"Honey bee genotypes and the environment" [32]. Two very interesting conclusions might be drawn:

"The conclusions from this comprehensive field experiment all tend to confirm the higher vitality of the local bees compared to the non- local ones, indicating that a more sustainable beekeeping is possible by using and breeding bees from the local populations. This may seem logical and obvious to many bee scientists, but has not been proven on such a wide scale before. This conclusion may also come as surprise to some beekeepers who believe that queens purchased from sources outside their own region are in some way “better” than the bees they already have in their own hives. We hope that our results may provide them with additional information and entice the community to regard benefits other than the mere amount of honey produced in a season as important."

"There is now growing evidence of the adverse effects of the global trade in honey bees, which has led to the spread of novel pests and diseases such as the varroa mite and Nosema ceranae. We hope that the evidence provided within the papers of this Special Issue will inspire beekeepers and scientists to explore and appreciate the value of locally bred bees, by developing and supporting breeding programmes. Damage from importations may arise from accompanying pests and pathogens, but it is also inevitable that introduced bees represent a burden to the genetic integrity of local populations. The spread of imported genes into the local population is likely, and the resulting increase in genetic diversity is not universally beneficial. Since maladapted genes will be selected against, this process may well in the short term contribute to colony losses, and is in the long term, unsustainable."

UK bans the importation of package bees

On a final note a news item (February 2021) stated that DEFRA in the UK was banning the importation of bee stocks from Italy into the UK. DEFRA is able to do this with the UK now having left the EU.

An interesting article by DEFRA attempts to clarify the issue on the importation of honey bees into Great Britain:

"Bee Importation"

"Honey bee genotypes and the environment" [32]. Two very interesting conclusions might be drawn:

"The conclusions from this comprehensive field experiment all tend to confirm the higher vitality of the local bees compared to the non- local ones, indicating that a more sustainable beekeeping is possible by using and breeding bees from the local populations. This may seem logical and obvious to many bee scientists, but has not been proven on such a wide scale before. This conclusion may also come as surprise to some beekeepers who believe that queens purchased from sources outside their own region are in some way “better” than the bees they already have in their own hives. We hope that our results may provide them with additional information and entice the community to regard benefits other than the mere amount of honey produced in a season as important."

"There is now growing evidence of the adverse effects of the global trade in honey bees, which has led to the spread of novel pests and diseases such as the varroa mite and Nosema ceranae. We hope that the evidence provided within the papers of this Special Issue will inspire beekeepers and scientists to explore and appreciate the value of locally bred bees, by developing and supporting breeding programmes. Damage from importations may arise from accompanying pests and pathogens, but it is also inevitable that introduced bees represent a burden to the genetic integrity of local populations. The spread of imported genes into the local population is likely, and the resulting increase in genetic diversity is not universally beneficial. Since maladapted genes will be selected against, this process may well in the short term contribute to colony losses, and is in the long term, unsustainable."

UK bans the importation of package bees

On a final note a news item (February 2021) stated that DEFRA in the UK was banning the importation of bee stocks from Italy into the UK. DEFRA is able to do this with the UK now having left the EU.

An interesting article by DEFRA attempts to clarify the issue on the importation of honey bees into Great Britain:

"Bee Importation"

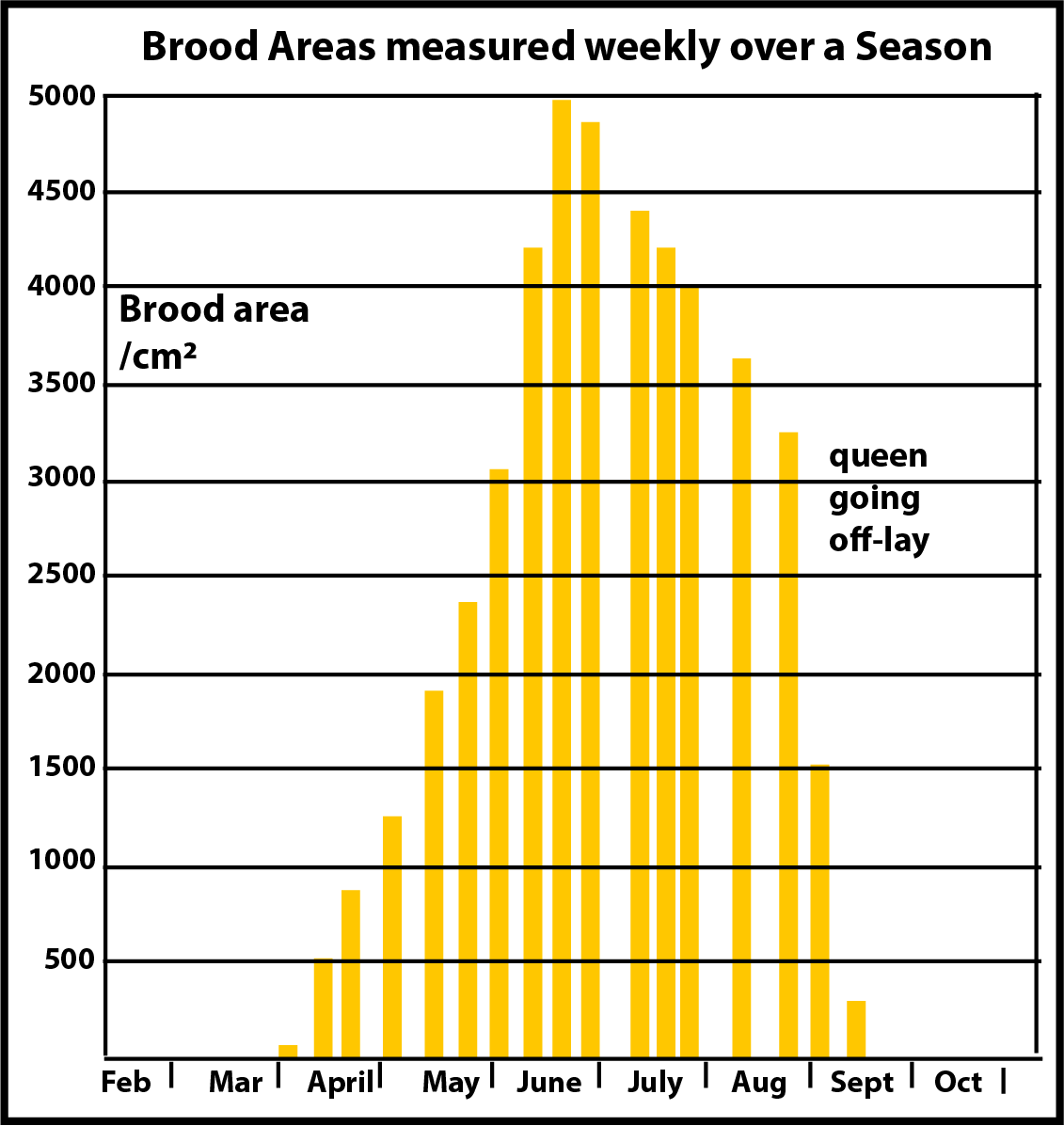

The diagram illustrates a typical annual brood pattern for my black bees in north-west Lancashire. Here winters are very wet and cold and summers on the cool side. However, the bees cope well with these condition and can often be seen flying in winter when the temperature is only 6°. Perhaps this should not be too surprising when it is realized that ancestors of these bees survived the last ice age and other relatives came through Russian winters.

The brood pattern (measured on a weekly basis) shows that for 6 months of the year October to March very little brood might be expected. The queen is relatively late in starting to lay compared to other imported bees, and that she rapidly goes off lay during September.

In the autumn the bees have no brood to feed and spend all their efforts in bringing in copious amounts of pollen to ensure the winter bees are well fed for the months ahead and ready to be able to feed the new brood in late March.

The brood pattern clearly reflects the availability of the local flora. There are only trees and wild flowers in this part of the country. The first nectar is available in April from the dandelion and the last in September from the Himalayan balsam. However, the late ivy is a valuable source of rich nectar and pollen.

The brood pattern (measured on a weekly basis) shows that for 6 months of the year October to March very little brood might be expected. The queen is relatively late in starting to lay compared to other imported bees, and that she rapidly goes off lay during September.

In the autumn the bees have no brood to feed and spend all their efforts in bringing in copious amounts of pollen to ensure the winter bees are well fed for the months ahead and ready to be able to feed the new brood in late March.

The brood pattern clearly reflects the availability of the local flora. There are only trees and wild flowers in this part of the country. The first nectar is available in April from the dandelion and the last in September from the Himalayan balsam. However, the late ivy is a valuable source of rich nectar and pollen.

Value of the local bee